- 06 December, 2022

- 0 Comment(s)

- 1050 view(s)

- লিখেছেন : Amartya Banerjee

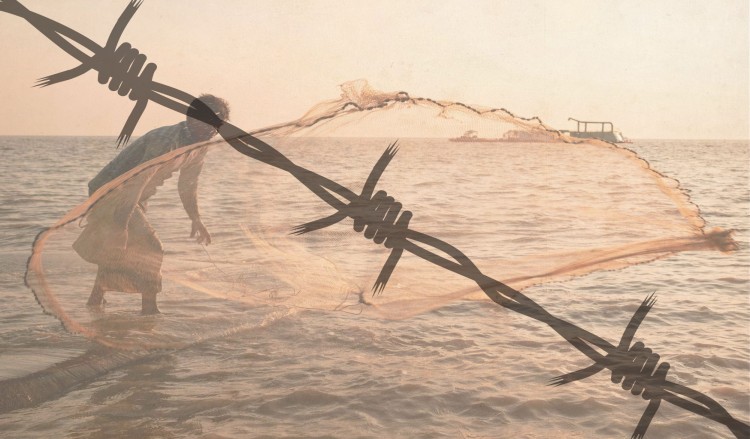

We can only wonder what Rokeya could have said, if she would have been here with us, at such times when Islamic Republic of Iran is burning with nationwide protest activities against the country’s notorious Hijab regulation. Spectators are holding up banners in support of Mahsa Amini at the Football World Cup stadiums. The games are being played in Qatar, an Islamic country again, whose social policies are strongly against the LGBTQ community standards accepted elsewhere. Apparently the world of Rokeya seems to have come a long way forward since her times and yet, for most of her people, the darkness remains.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain was a reformer, feminist thinker, writer and educationist, who worked for literacy and education amongst Muslim women. She was born on 9 th December, 1880 to a Bengali Muslim family in the village of Pairaband, Rangpur, now in Bangladesh. It is not our intention to merely sketch another biographical narrative of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. Rather the objective here is to extract the reasons for which the lady stood radically apart, outside the conventional list of peers and social workers. She continues to remain a unique example in the history of Islamic reform movements, particularly for her works related to education of Muslim women.

Education and organized religion are never good bedfellows as far as the history of humankind is concerned. Numerous examples can be cited for every major religion, quantitatively justifying this proposition. Whenever one utters the term ‘organization’ - consequently comes the idea of people moving in and gathering together, forming certain amount of cohesion amongst them, and later on as it happens in religions – unquestionably accepting what the preachers recite. The idea of cohesion and acceptance are the fundamental tenets of anything ‘organized’ – and in case of religions, the strength of cohesion or any whatsoever reason for acceptance, are primarily derived not from any logical appreciation but from something much more qualitative in nature. We have named this premise as ‘Collective Faith’ or ‘Biswas’ in Bengali, and which after many years of evolution (?) continues to exist as a murderous weapon in the hands of the mullahs or purohits. On the other hand, it also continues to exist as the most intoxicating beverage of ignorance in the hands of the general population. Cohesion or acceptance based solely on devout faith is an entity that must be feared. This drives a population into ignorance. Such ignorant faithfulness deprives the characteristics of logical thinking to the generation of followers, and consequently moulds them towards blind belief which is detrimental to them as well as for the others around.

Rokeya rightly proposed the solution as education. The lethargic addiction to collective faith-based narratives can only be countered with proper education based on logic, science andrudimentary mathematics, which pushes and nurtures our abilities to think, analyze and deduct for our perceptions. Rokeya, apart from being a thinker, writer or critic, must be primarily anduniquely remembered for her distinct and dedicated agenda of education amongst the poorest of the poor and the most ignorant of the society. While being a writer, she never forgot her role as a reformer and educationist, the fact which is consistently depicted in her works. In the year 1911, when Mohun Bagan Football Club won their first IFA Shield trophy after defeating the East Yorkshire Regiment in the finals, thus heralding a new age in the history of nationalism in Indiaand Bengal, a Muslim lady, recently widowed by the sad demise of her husband and absolutely irritated by property disputes that followed between her and her in-laws, came to Kolkata and established what was to become the first ever educational institution for Muslim women in the metropolis. Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ High School was first established in Bhagalpur, in the memory of Rokeya’s late husband Khan Bahadur Sakhawat Hossain and it started with only five students at the beginning. Later, due to property related disputes with her husband’s family Rokeya moved to Kolkata, in 1911, two years after her husband’s death and re-established the school in the city. She ran the institute for 24 years. During this period she literally carried out door-to-door campaigns by herself to persuade Muslim families, barred by the evil practice of confinement or ‘purdah’ as it is described in the society, to send their girls to school. At nights, this upright woman visited the neighbourhoods, persuaded and convinced the women and the male ‘heads’ of their families to accept the necessity of education. She vehemently fought with the elders and other members of the society to make them realize, the utility of education to be imparted upon their wards. This relentless campaign of education finally bore fruit, and the heritage of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, in the form of Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ High School still stands at the heart of the metropolis as one of the prime institutes of education and learning, not solely for the Muslims but for girls coming from each and every religion today.

Education is the sharpest weapon that one can use against the tyranny of ignorance, the standard hallmark of any ‘organized religion’; that idea of ‘organized religion’ which must be fought and challenged on every sphere of the society today, and also at every epoch of humanity without the slightest possible hesitation.

One can only desire to meet her today, and expect her to publish one or two of her literary pieces to celebrate the protests and uprisings of the deprived women in Iran and Afghanistan. The legend of Rokeya – seems to have reignited through the protests in these two countries under radical Islamic rule as of now, but the clang of the bells to eradicate the rulers can be heard. A change of time is in order.

The confinement has been broken through. The abolition of ‘purdah’ as a global phenomenon is no more a distant reality from our perceptions. The war that has continued for almost a hundred and forty years since Rokeya’s birth must now see its culmination. The feminist science fiction novella entitled ‘Sultana’s Dreams’ (1908) which was penned by Rokeya, was not a mere fiction

– but was an eye-opener for all the girls of her times as well as for ours. The satirical depictions in ‘Abarodhbasini’ (1931) were written to pinch and humiliate the society, only to make it rise from its age-old slumber and accept reason against collective faith, idea of logic against beliefs and superstitions, science and health against ignorance and unhealthy practices.

[***]

We have come far, further than we ourselves can comprehend. After a hundred and forty years since Rokeya’s times – today we can recite boldly from another man’s writings, and I quote (only slightly changing the narration in present tense, deliberately for the sake of this article’s objective),

“Revealation is to be understood as an interior, subjective event, not an objective reality, and a revealed text is to be scrutinised like any other text, using all the tools of the critic, literary, historical, psychological, linguistic and sociological. In short, the text is to be regarded as a human artefact and thus, like all such artefacts, prey to human fallibility and imperfection.” [1]

Thus rendered moot the argument of the believers to place logic ahead of collective faith, thus re-establishing the omnipotence of science and education against all forms of confinement, physical, mental or metaphysical, whatsoever the clerics dare to preach.

[1] ‘Joseph Anton – A Memoir’, Salman Rushdie, Published by Vintage, 2013

.jpeg)

0 Comments

Post Comment